02 Nov A Giant Home: Sense of Belonging within the Streets (First Prize)

First Prize: “Re:Imagine, Re-Design, Re-Claim” Essay Competition for #UrbanOctober2021

Honourable Mention, Photo/Illustration Competition

Theme: Mitigating Migration: Impact of Resettlement on Gendered Bodies

Sense of belonging refers to a feeling of being accepted which, in a public space creates a feeling of agency or ownership of that space. Physically, this concept is directly dependent on the range of access to the space wherein familiarity plays a

major role. Gendered bodies thereby differently use spaces that are alien to them. This was evident in the study of low-income women vendors based in Kochi, Kerala. Most of the women vendors had migrated from other settlements to Vytilla city in Kochi a few years back and vegetable vending was their only means of livelihood. Most of them had resettled along with their families and stayed closer to the vending location. The following observations and inferences would be based on the study done in Vytilla, Kochi, Kerala.

Vending as an activity is observed to have certain predefined gender norms. While women vendors sold perishable goods like vegetables and cooked food, male vendors were mostly into selling non-perishable goods like lottery tickets. Although both men and women vendors shared the same space for vending, the lack of access to vending carts for women had them sit on the pavements with the goods with no roof on top. This was in contrast to the space created by male vendors with their own vending carts, a chair, and an umbrella for shade.

Comparing the two vendors, the space chosen by female vendors for vending was additionally dependent on the presence of access to sanitation facilities. The statement is ironic because there were no formal sanitation spaces available on site. Lack of public toilets was a major concern for most of the resettled women vendors since they

could only stay up in the vending space as far as their bladder would allow them. But interestingly, few of the established women vendors had their vending space located close to a tea shop with a familiar owner for her sanitary needs. The social connection she has created with the tea shop owner accounts for her usage of the shop’s restroom. Here, again the factor of familiarity plays a major role.

Though women and men vendors spent the same amount of time on the streets, the movement and interactions for women vendors were far lesser than for men vendors. Male vendors loitered in between the vending hours, to tea shops and other shops in proximity to the selling space and found scope for leisure in between work. In fact, men created a network of leisure, influenced by the presence of a large number of men as daily street accessors wherein chai drinking was their major leisure activity. Social activities like chai drinking had an exclusion for women which is mainly accounted from the restriction of women’s access to leisure in public space from a social lens. Apart from the social construct, the design of the tea stall as such had a very narrow entrance, which usually gets crowded by the loitering men and their vehicles all throughout the day making it less welcoming for a woman. Hence, the spatial design of the tea stall reinforces the social ideology of exclusion of women in the leisure space. Hence, the women vendors almost never really occupied the major leisure spots. In fact, women’s access to leisure was restricted in the primary streets.

Most of the vendors stayed at housing colonies close by which were on the residential streets, a few kilometers away from the vending site. In contrast to the usage of primary streets, the same vendor women were observed to use the residential streets differently. Although the site did not offer a leisure space in the residential streets, women found scope for interactions with each other in the residential streets. For a woman seeking leisure, the observations showed a dependency on the sense of enclosure which was impacted by the scale of the space, pavement material, and the visual connection to the residential buildings. Easy access to residences is another factor that influenced women’s access to leisure. The purpose of keeping eyes on children playing provided opportunities of leisure in the evenings for women in the residential street.

Learnings from the site mappings reveal a strong correlation between the ability to experience leisure on the street and the perception of belongingness. Since women found belonging in and close to their homes, the challenge is to create the same sense of enclosure in the primary street as well where the migrated vendors could feel the sense of ownership.

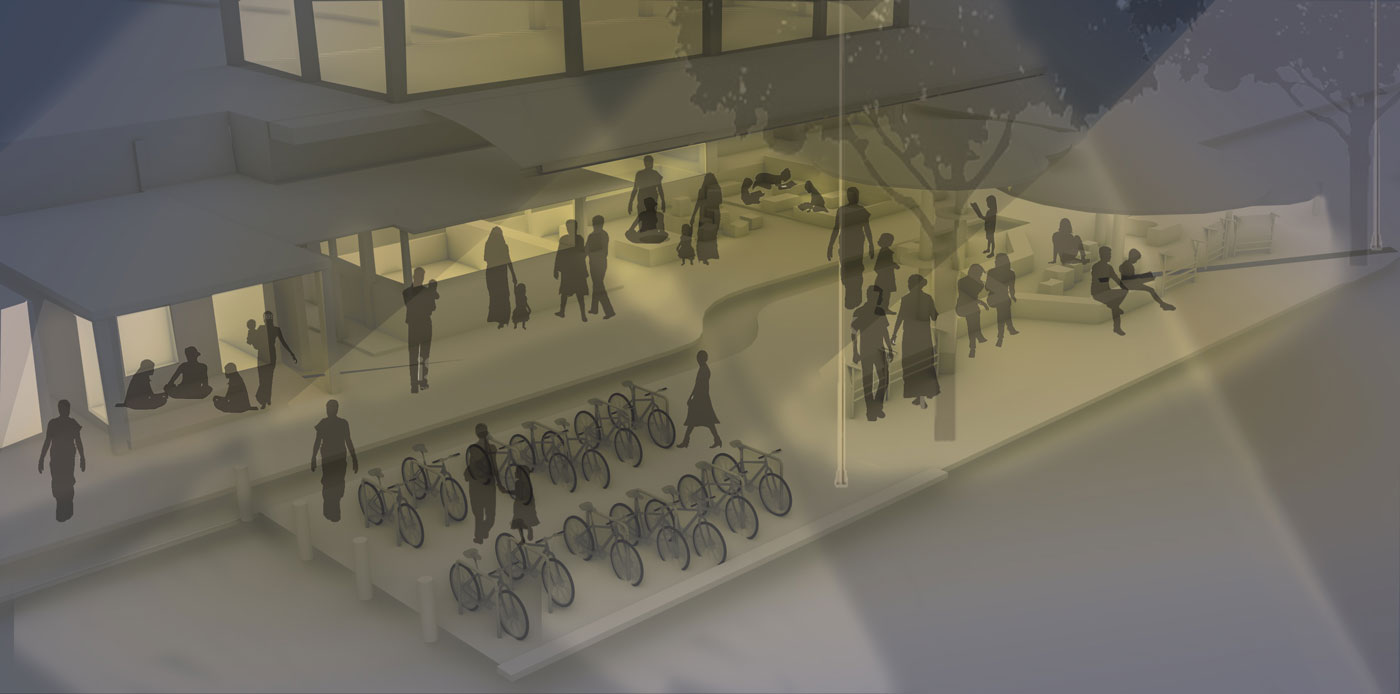

Reimagination of the vending space

Does formalizing of the vending sector help give greater agency to the migrated vendors?

The proposed vending space would be managed by the Self Employed Women’s Association. This is based on the issues faced by lower-income women in the informal sector currently, which results in a lack of ownership of the space. Formalizing aims at designating a space for women’s vending by providing the essential infrastructure and security to the women vendors.

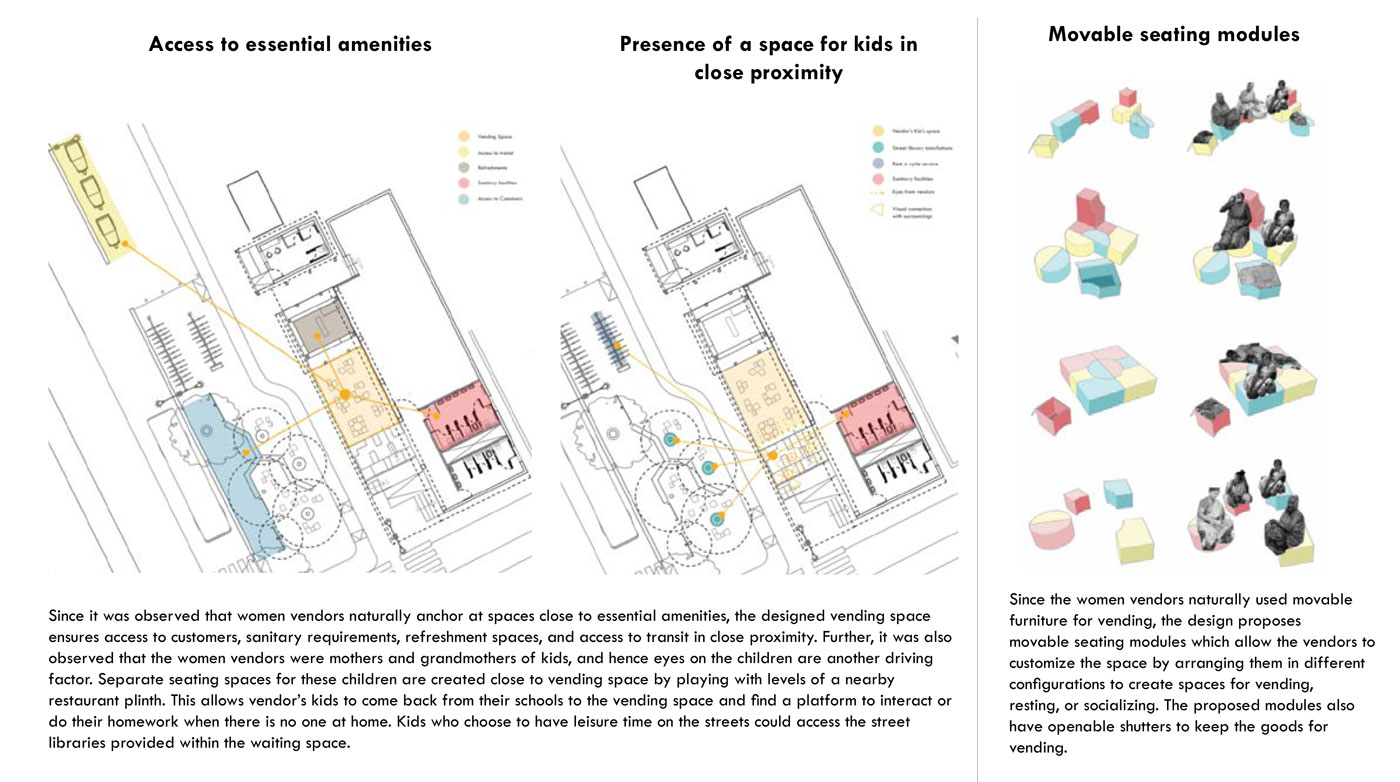

Since it was observed that women vendors naturally anchor at spaces close to essential amenities, the designed vending space ensures access to customers, sanitary requirements, refreshment spaces, and access to transit in close proximity. Further, it was also observed that the women vendors were mothers and grandmothers of kids, and hence eyes on the children are another driving factor. Separate seating spaces for these children are created close to vending space by playing with levels of the restaurant plinth. This allows vendor’s kids to come back from their schools to the vending space and find a platform to interact or do their homework when there is no one at home. Kids who choose to have leisure time on the streets could access the street libraries provided within the waiting space. The provision of MyByk spot on the site as an addition to the existing network in Kochi also aids for their leisure. This has an app-based service but would work for vendors’ kids with the Licence ID provided by SEWA.

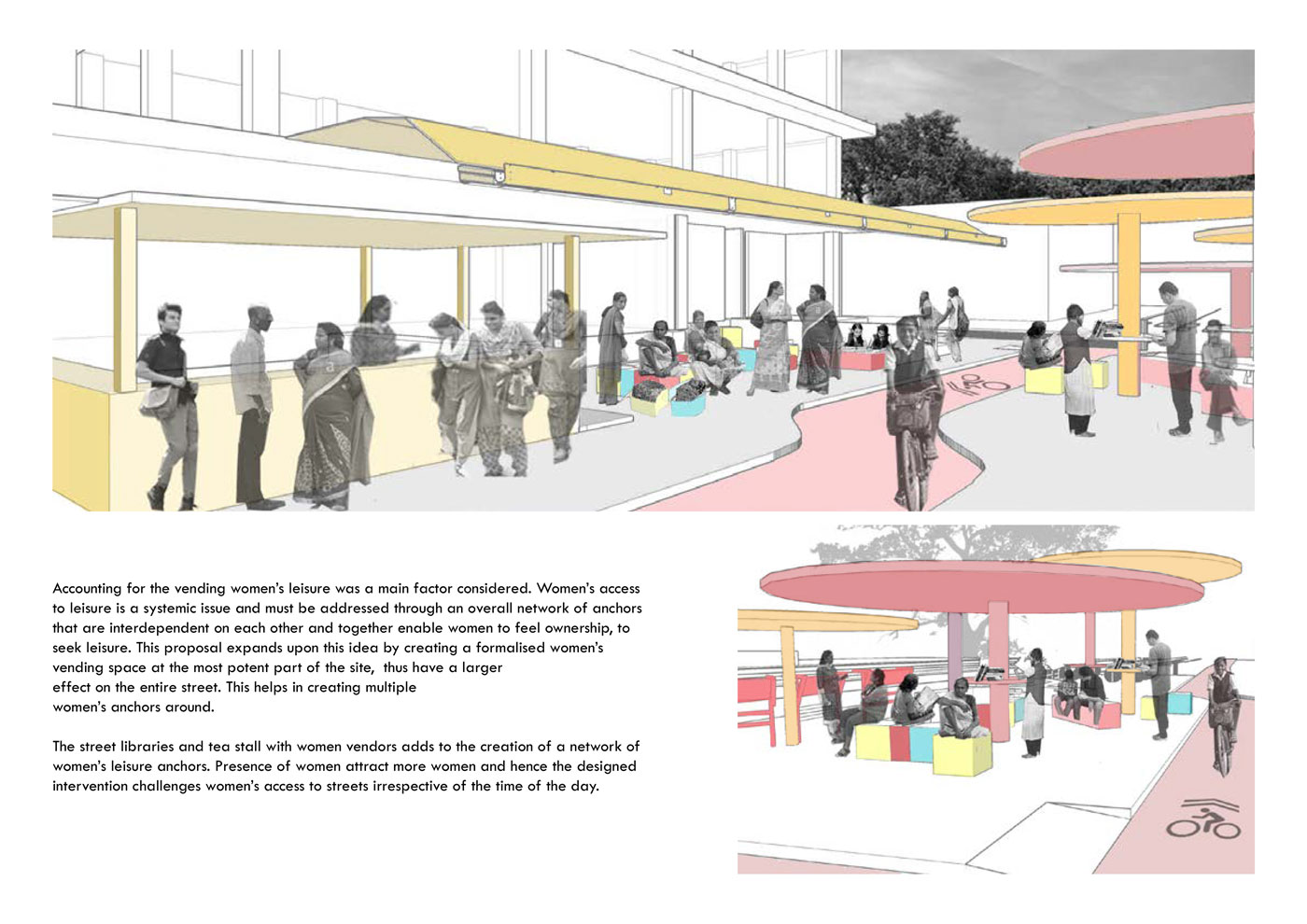

Since the women vendors naturally used movable furniture, the design proposes movable seating modules which allow the vendors to customize the space by arranging them in different configurations to create spaces for vending, resting, or socializing. The proposed modules also have openable shutters to keep the goods for vending. Anchoring the vending space close to a tea stall provides easy access to leisure for the women vendors. It was observed in the existing tea stall that a single approach crowded with men at times obstructed women’s access to leisure. Though few women did occupy the tea stall at less crowded times of the day, the existing design, with its scale and visual barriers, limited the occupancy of women. The design spatially aids for uncontested access to tea stalls for women, if they wish to and re-imagines the culture of tea drinking for all.

The proposed tea stall would have three separate approaches and a designated parking space that prevents the organic parking of vehicles at the shopfront. The orientation of the tea stall also ensures a view of the arriving bus and a clear way to walk in and out. Since storage and transport of perishable goods are currently faced with issues by women vendors, the existing cooling storage in the tea stall could be utilized for the storage of the leftover goods so that it acts as a natural anchor to the women. The dual functions of the tea stall could also challenge the stereotyped definition of a tea stall as a male anchor.

The proposed idea is just the start of reimagining a giant home that offers a sense of belonging to its diverse users irrespective of how familiar the space is. Women’s access to leisure is a systemic issue and must be addressed through an overall network of anchors that are interdependent on each other and together enable women to feel ownership, to seek leisure, thus beginning to question could spaces begin to impact social behavior instead of the normally understood norm of social impacting spatial.

About the Author

Vrinda KV Is pursuing a B.Arch degree at CEPT University, Ahmedabad and dreams of working in a creative and dynamic field. Born and brought up in a small town in Kerala, she has always been triggered by the gendered social norms and stereotypes followed there. Doing an urban planning studio titled ‘Ungendering the Everyday City’ at CEPT, guided by Sahiba Gulati, Bhagyashree Ramakrishnan, and Mallika Gupta, helped her apprehend how the gendered streets are not just an outcome of social behavior and realize that there is something that a designer can do to bring a change. She strongly believes that smaller steps can lead to bigger changes and hence would continue trying until the world becomes ‘a giant home’ that we all imagine.

Vrinda KV Is pursuing a B.Arch degree at CEPT University, Ahmedabad and dreams of working in a creative and dynamic field. Born and brought up in a small town in Kerala, she has always been triggered by the gendered social norms and stereotypes followed there. Doing an urban planning studio titled ‘Ungendering the Everyday City’ at CEPT, guided by Sahiba Gulati, Bhagyashree Ramakrishnan, and Mallika Gupta, helped her apprehend how the gendered streets are not just an outcome of social behavior and realize that there is something that a designer can do to bring a change. She strongly believes that smaller steps can lead to bigger changes and hence would continue trying until the world becomes ‘a giant home’ that we all imagine.